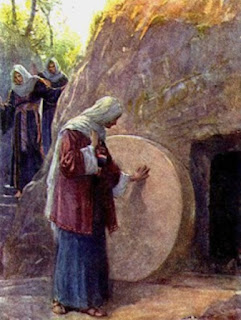

Empty but full....

What did happen historically to the dead body of the crucified Jesus? Was his body buried as firmly testified by NT gospel stories? At first, John Dominic Crossan simply judged that “nobody knew what had happened to Jesus’ body.”[1]

He also wrote: “[A]n indifferent burial by Roman soldiers becomes”, in the early Christian reflection, “eventually a regal entombment by his faithful followers.”[2]

Crossan’s hardest judgment, however, came out later on: if Jesus’ body had been left on the cross, it would have been eaten up by wild beasts, carrion crows and birds of prey; or, if it had been buried by Roman soldiers as part of their job in a shallow grave barely covered with dirt and stones, the scavenger dogs that had been waiting for their food would have the body as their meal to help finish the Roman brutal job.

For Crossan, the stories about Jesus’ burial by his friends are totally fictional and unhistorical accounts in which the Jewish legal injunction about burying the executed man on the same day as recorded in Deuteronomy 21:22-23 functioned as the formative force.

Crossan baldly states that “Mark created that burial by Joseph of Arimathea in 15:42-47. It contains no pre-Markan tradition”, and “the empty-tomb story is neither an early historical event nor a late legendary narrative but a deliberate Markan creation.”[3]

Crossan recently (1999), however, has modified his position. As to the burial, he states “that Jesus was buried is certainly possible and, if Paul intends ‘that he was buried’ (1 Cor 15:4) as received tradition, it may even be probable.[4]

But the horror is this: the major alternative to the body abandoned on the cross is the body dumped in a limed pit.[5]

For Crossan, in his earlier thought, the stories of Jesus’ resurrection and apparition (= resurrectional, revelatory appearances in and through the disciples’ vision[6]) are not stories about factual, historical happening, but fictional stories created literarily and ideologically in connection with the political power struggle within the authoritative leadership of the early Christian communities.

They are therefore not stories about Jesus’ power over death but about the apostles’ political power over the community.[7]

Helmut Koester also has noted that “the written passion narratives that were circulated, as well as the writings that became Gospels, reveal a political interest.”[8]

The genre of the resurrection appearance story itself, as Kelber has pointed out, would have been suited to the practices of simultaneously instituting and enhancing esoteric knowledge concerning Jesus and apostolic authority.[9]

However, with regard to the resurrectional apparition, on the basis of writings such as Virgil’s Aeneid Book 2, the assertion of the pro-Christian defender Justin Martyr, in 1 Apology 21, as well as the passage from the anti-Christian attacker Celsus, On the True Doctrine, Crossan recently concludes that in the general Mediterranean culture in antiquity, at the time of Christianity’s beginnings, post-death apparition and ascension into heaven were accepted as possibilities rather than as completely unique and abnormal events.[10]

Furthermore, using the insights of studies in the psychosocial and cross-cultural anthropology of comparative religion, and the insights drawn from modern psychiatric studies in grief and bereavement, Crossan draws the conclusion that a vision of a deceased person alive again is a possibility common to our humanity, a possibility hard-wired into our brains, factually and historically happened both in the first century and in the modern times.[11]

Crossan even can speak about the “bodily” or “fleshly” resurrection of Jesus; but, for him, it “has nothing to do with a resuscitated body coming out of its tomb. And neither is it just another word for Christian faith itself.” It “does not mean, simply, that the spirit of Jesus lives on in the world. And neither does it mean, simply, that the companions or followers of Jesus live on in the world.”

Rather, it means that “the embodied life and death of the historical Jesus continues to be experienced, by believers, as powerfully efficacious and salvific in this world. That life continues, as it always has, to form communities of like lives.”[12]

With this perspective, Crossan finally clearly interconnects the presence of the resurrected Jesus with that of the historical Jesus. Hence, the transcendence and the immanence intersect.

☆ Paragraphs edited May 20, 2022

Notes

[1] John D. Crossan, Historical Jesus, 394; in harmony with, a.o., Gerd Lüedemann, The Ressurrection of Jesus: History, Experience, Theology (SCM Press, 1994) 180.

[2] Crossan, “Empty Tomb and Absent Lord” in Werner H. Kelber, ed., Passion in Mark (1976) 152 (135-152).

[3] Birth of Christianity, 555, 558 (emphasis original); Jesus, 123-127, 152-158, 160; Four Other Gospels, 153f., 164.

[4] Cf. Gerd Lüdemann, De Opstanding van Jezus: Een Historische Benadering (Baarn: Ten Have, 1996) 38: “... omdat de tradities eenstemming verhalen van een kruisafname (ook I Kor. 15:4 gaat daarvan uit). Daarom zou de begrafenis van Jezus kunnen behoren tot de uitzonderingsgevallen, waarbij de Romeinse autoriteiten het lijk vrijgaven.”

[5] Crossan, “Historical Jesus as Risen Lord” in The Jesus Controversy. gen. ed. Gerald P. McKenny (RLS; Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Trinity Press, 1999) 17 [1-47]; Birth of Christianity, 528, 555. In this regard, Crossan refers to Marianne Sawicki, Seeing the Lord: Resurrection and Early Christian Practices (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1994) 180, 257.

[6] Crossan uses the terms vision and apparition interchangeably (“Historical Jesus as Risen Lord”, 6).

[7] That is, they give witness to the trajectory of Jesus’ revelatory apparition, moving the emphasis of the revelation slowly but steadily and hierarchically from general community to leadership group to specific leaders with apostolic authority—a trajectory originating, in a sense, from Paul which was, later in the canonical gospels’ context, colored by questions, debates, and even controversies and deliberate political dramatizations over direction, leadership, and authority within the early Christian communities. See Historical Jesus, 395-416; Jesus, 165ff.; Who Killed Jesus?, 202ff.

[8] Koester, “Writings and the Spirit: Authority and Politics in Ancient Christianity” in Harvard Theological Review 84:4 (1991) 369 [253-372]. On p. 359: “the so-called theology of Paul’s letters must... be understood as secondary when compared to the political intent of the letter”; on p. 368: “the development of the gospel literature was a process that is analogous to the establishment of the authority of Christian epistolary literature.”

[9] Kelber, “Narrative and Disclosure: Mechanisms of Concealing, Revealing, and Reveiling” in Semeia 43 (1988) 6 [1-20].

[10] “Historical Jesus as Risen Lord”, 6f., 26-31. For surveys of the literary history of the genre of the resurrection stories, see , e.g., Johannes Leipoldt, “The Resurrection Stories” in Journal of Higher Criticism 4:1 (1997) 138-149; Gregory J. Riley, Resurrection Reconsidered: Thomas and John in Controversy (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995) 7-68.

[11] “Historical Jesus as Risen Lord”, 6-7; Jesus, 87-88; “Why Is Historical Jesus Research Necessary?” in James H. Charlesworth and Walter P. Weaver (eds.), Jesus Two Thousand Years Later (Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 2000) 17-18 [7-37]. Cf. Lüdemann, De Opstanding van Jezus, 176-178 [114-178].

[12] “Historical Jesus as Risen Lord”, 45-46.